The dusty railway lines of South London stretch out like weathered veins across the suburban landscape. They carry the same dreams of escape that they have carried for generations. It was along these tracks that two of Bromley’s most transformative artistic voices found their way out. Hanif Kureishi and David Bowie, boys from the same streets, separated by a decade. And yet united by their determination to transform the confines of the suburbs into art.

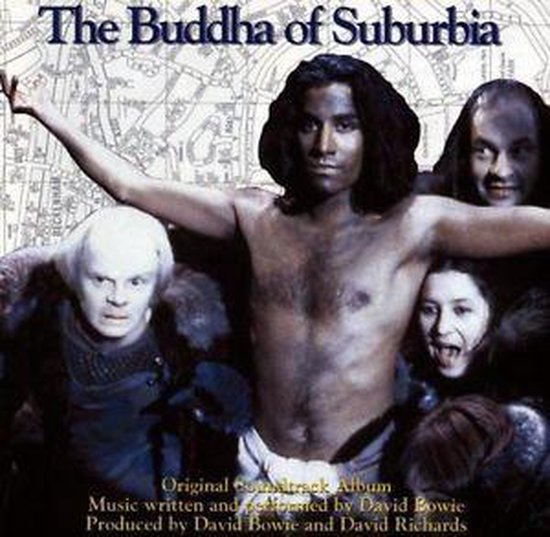

The Buddha of Suburbia: Kureishi’s Words, Bowie’s Notes

Bromley is more than just a backdrop in Kureishi’s semi-autobiographical novel “The Buddha of Suburbia” from 1990. It is a character in itself, the place that protagonist Karim Amir both loves and wants to escape. The novel, with its mixed Anglo-Pakistani protagonist navigating through the cultural landscape of 1970s London, pushed boundaries in British literature with its portrait of suburban life.

On a cold winter day in 1993, something special happened. Kureishi had interviewed David Bowie during the promotional tour for “Black Tie White Noise.” At the end of their conversation, Kureishi casually mentioned that he was adapting his novel for BBC television. He asked if they could use some older Bowie songs like “Fill Your Heart.” Bowie nodded. Then, gathering his courage, Kureishi asked if the singer might want to contribute original material.

Sometimes the most beautiful things arise from chance encounters. After viewing some rough footage, Bowie was so moved that he decided to do much more than just provide some background music. Together with multi-instrumentalist Erdal Kızılçay, he retreated to Mountain Studios in Montreux. There, overlooking the Swiss lake, he completed an entire album in just six days. It became a collection of sounds that he would later describe as ‘dozens of personal memories from the seventies.’

The result was a hidden gem in Bowie’s rich catalogue, “The Buddha of Suburbia.” Released in November 1993, despite sharing the title, it was not a soundtrack but an artistic dialogue with Kureishi’s novel. A meditation on growing up in the suburbs, searching for cultural identity, and the urge to escape the confines of predictable lives.

A Spiritual Connection

The title song forms a perfect bridge between these two suburban artists. Bowie weaves memories of his youth in South London together with musical echoes from his past. The octave-lower vocal style from his glam rock period returns, along with a guitar fragment reminiscent of “Space Oddity” and a mysterious, incantatory repetition of ‘Zane, zane, zane, ouvre le chien’ that had appeared earlier in “All The Madmen.”

This self-conscious play with memories and identities fits seamlessly with the themes of Kureishi’s novel. As literary scholar Claire Allen has noted, Kureishi’s protagonists are drawn to figures like Prince and Bowie precisely because these artists embody what they seek: ‘the ideology of mutability in musical and identity creation.’ Bowie’s career, in which ‘almost every album sees him adopt a new persona,’ demonstrates the possibility of self-invention.

The connection between the two artists goes deeper than just a shared birthplace. Kureishi’s story of a boy struggling with his mixed heritage and his place in the world struck a chord of recognition with Bowie. The album, which critic Julian Marszalek described as ‘a consolidation of Bowie’s powers as singer, songwriter and producer,’ sounds like the sound of an artist rediscovering his voice by looking back at his beginnings.

David Bowie: A Never-ending Journey

Although the album had little commercial impact – it only reached number 87 in the UK charts – it was recognised by critics as a hidden masterpiece. Bowie himself called it his favourite album in 2003. The experimental soundscapes, the seamless blending of pop, jazz, ambient and rock, and the nostalgic but never sentimental atmosphere show David Bowie at one of his most personal moments.

The two artists became friends, and years later Kureishi reflected on what connected them: ‘We grew up in a time when you had to have a fixed identity,’ he said, ‘And suddenly someone like Bowie shows up in a dress and high heels, and you thought: “He knows me, he understands me, and he’s going to take us away from here.”‘

The music of “The Buddha of Suburbia” sounds like a soundtrack for a journey that never ends – a journey from Bromley to the stars and back. In both Kureishi’s words and Bowie’s notes, we find a manual for navigating between worlds, cultures, and identities. Their work offers a blueprint for anyone who has ever felt trapped in the suburbs of existence, searching for a way out or a way in.

This unexpected chapter in Bowie’s career – creating from literature rather than from his own persona – shows why he was always more than just a pop star. The way he translates Kureishi’s story into a tapestry of sounds and atmospheres underscores his literary sensibility and his ability to absorb and transform sources from different art forms.

And so begins our story of Bowie in images – not with the glamour of superstardom or the glitter of film premieres, but with an unexpected collaboration that arose from a chance meeting between two suburban boys who slipped away along the railway line to a bigger world.

Space Oddity and the Early Years (1969-1972)

David Bowie’s musical journey began long before he became internationally famous. His breakthrough came with “Space Oddity” in 1969, a song that perfectly coincided with the Apollo 11 moon landing. The song reached the top five in the United Kingdom and marked the beginning of Bowie’s fascination with spatial themes, isolation, and alienation – themes that would follow him throughout his career.

Although Bowie did not appear in many films at that time, his music was already cinematic. The narrative structure of “Space Oddity” and later songs like “Life on Mars?” created mini-film scenes within the music itself. These early songs would later be frequently used in films and television to underscore moments of alienation, melancholy, and longing.

Ziggy Stardust: The Birth of an Alien Rock Icon (1972-1973)

The creation of Ziggy Stardust in 1972 marked a revolutionary step in Bowie’s career. This androgynous, alien alter ego was a deliberate construction. It was inspired by diverse sources such as British singer Vince Taylor, Texan musician Legendary Stardust Cowboy, Japanese kabuki theatre, and artists like Iggy Pop and Lou Reed.

With Ziggy Stardust, Bowie defined the archetype of the messianic rock star. A figure who comes to Earth as a sort of alien being before an impending apocalypse to bring a message of hope. The concept included the rise of the star, his success, and ultimately his downfall through his ego and excesses.

The cinematic qualities of the Ziggy Stardust character were unmistakable. Bowie’s performance on BBC’s Top of the Pops in July 1972, in which he performed “Starman,” is considered a defining cultural moment comparable to The Beatles’ appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964.

This era culminated with the concert at Hammersmith Odeon on July 3, 1973. There came the shocking announcement that this “would be the last show he would ever do.” This moment was captured in D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary “Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.” A film that remained in post-production for years before it was released in 1983.

The Berlin Trilogy: Experimental Sounds in a Divided City (1976-1979)

After his Ziggy Stardust period and a brief phase as the Thin White Duke, Bowie moved to Berlin in 1976. According to him, to escaped his drug addiction in Los Angeles and found a new artistic direction. He described Berlin as a ‘kind of sanctuary.’ Bowie said: ‘Berlin has the strange ability to make you write only the important things.’

The subsequent three albums – “Low” (1977), “Heroes” (1977), and “Lodger” (1979) – are collectively known as the ‘Berlin Trilogy.’ These albums, created in collaboration with producer Tony Visconti and Brian Eno, represented a radical musical change of course. It moved toward experimental, ambient, and electronic sounds, inspired by German krautrock bands such as Kraftwerk, Neu! and Can.

Although not all three albums were recorded entirely in Berlin, they capture the spirit of the divided city and Bowie’s transformation. “Low” was largely recorded in France, “Lodger” in Switzerland and New York. “Heroes” in particular, has become emblematic of this period. The title song was inspired by Bowie’s view of the Berlin Wall from Hansa Studios.

The music from this period has left an indelible impression on filmmakers. The atmospheric, often instrumental pieces from “Low” and “Heroes” have found their way into countless films, including “Christiane F.” (1981). The grim German film about drug addiction in which David Bowie himself appeared, and for which he contributed music. The song “Heroes” has, in particular, become a favourite for filmmakers. It has been used in films such as “The Perks of Being a Wallflower,” “Moulin Rouge,” and in the TV series “Glee.” Often to underscore moments of transcendence and breakthrough.

Mainstream Success and Film Roles (1980-1986)

The 1980s marked a period of greater commercial recognition for Bowie. With hits like “Ashes to Ashes” (1980), “Under Pressure” (Queen, 1981) and “Let’s Dance” (1983), things went very well. The latter, produced by Nile Rodgers, was a success! His first single to reach the number one position in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

This period coincided with David Bowie in his most active years as an actor. He appeared in “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence” (1983) as Major Jack Celliers. But he also starred in the cult film “The Hunger” (1983). He also took on the iconic role of Jareth the Goblin King in Jim Henson’s “Labyrinth” (1986).

His duality as a musician and actor reached a peak during this period, with his film personas reflecting his musical personas. For “Labyrinth,” he contributed not only as an actor but also as a musician, with five songs he wrote for the film.

“Let’s Dance” has since found its way into many film scenes, including a memorable moment in “Top Gun: Maverick” (2022). There, it was used to underscore the reunion of Tom Cruise and Jennifer Connelly’s characters.

Later Years and Legacy (1987-2016)

Throughout the ’90s and 2000s, David Bowie continued to experiment with various musical styles, including industrial and jungle. He also continued acting, with roles as Andy Warhol in “Basquiat” (1996) and Nikola Tesla in Christopher Nolan’s “The Prestige” (2006).

His final album, “Blackstar” was released on his 69th birthday in 2016, two days before his death. It was accompanied by two highly cinematic music videos for the songs “Blackstar” and “Lazarus.” These videos, with their dark, filmic narratives, proved that Bowie’s ability to merge music and visual art remained intact until the end of his life.

In the years since Bowie’s death, his music has continued to resonate in films and television. Songs like “Modern Love” in “Frances Ha,” “Cat People (Putting Out Fire)” in “Inglourious Basterds,” and “Under Pressure” in “Aftersun.” They demonstrate that filmmakers continue to draw on Bowie’s rich catalogue to add thematic depth to their work.

The Cinematic Legacy of a Musical Visionary

David Bowie’s influence on music and cinema is immeasurable. Just as cinema shaped Bowie, David Bowie shaped cinema. Filmmakers such as Pedro Almodóvar, Wes Anderson, Todd Haynes, and Baz Luhrmann have all borrowed elements from Bowie’s cinematic music. But also from his alien glamour and his fearless creative spirit.

David Lynch used Bowie’s “I’m Deranged” from the album “Outside” (1995) for the opening and closing scenes of “Lost Highway” (1997). Thereby integrating Bowie’s music into the fabric of his enigmatic neo-noir.

Bowie’s ability to reinvent himself, both musically and visually, made him a pioneer in the use of persona and performance in pop music. As he said: ‘What I did with my Ziggy Stardust was package a completely credible, plastic rock ‘n’ roll singer, much better than the Monkees could ever fabricate.’

By considering his music as benchmarks in films and his film roles as reflections of his musical evolution, we gain a richer understanding of David Bowie’s artistic journey. From the astronaut Major Tom to the alien Ziggy Stardust. But also from the alienated traveller in Berlin to the Goblin King. Bowie’s transformations form a cinematic odyssey that has no equal in the history of pop music